… Helen Morgan opened in the Ziegfeld Follies of 1931.

In December 1930, noticing a dearth of annual revues in the works for the coming year, Ziegfeld began to assemble a production team and cast for a late May/early June production. Early reports pointed to Will Rogers as the star and Ruth Etting as the leading chanteuse.[i] By 1931, Rogers was too busy to seriously consider a stage production, much as he may have wanted to return to Ziegfeld. An attempt to secure Maurice Chevalier withered when the French star demanded a $10,000 a week salary.[ii] At the same time, Ziegfeld approached silent clown Harry Langdon to be his star comic. While Broadway stars like Rogers and Eddie Cantor were enjoying immense popularity in talking pictures, silent holdovers like Langdon saw their stars fade. However, Rogers proved unavailable and even Langdon’s price tag of $2,500 a week proved too much for Ziegfeld.[iii] Comic Joe Laurie, Jr. was another early mentions for the revue.[iv]

Helen came aboard on April 19.[v] After the previously announced Ruth Etting, Helen was the second principal to be confirmed.[vi] Helen’s run of the play contract cited a salary of $1,500 a week with a four-week notice clause for either party. Prior to signing with Ziegfeld, Helen’s name was on the short list of potential talent for The Third Little Show. It is unclear whether Helen turned down producer Dwight Dee Wiman or if he balked at hiring Morgan. In any event, Helen felt the need to make a grand and impressive entrance into the Music Box in a pink dimity gown on June 1, the opening night of The Third Little Show. The revue’s finale contained not one but four girls sitting upon pianos. Helen’s response was among the most demonstratively appreciative of those first nighters, but the stunt was far from new. John Murray Anderson had already placed multiple girls upon pianos in the Morgan manner in his Murray Anderson’s Almanac (August 14, 1929, Erlanger).[vii]

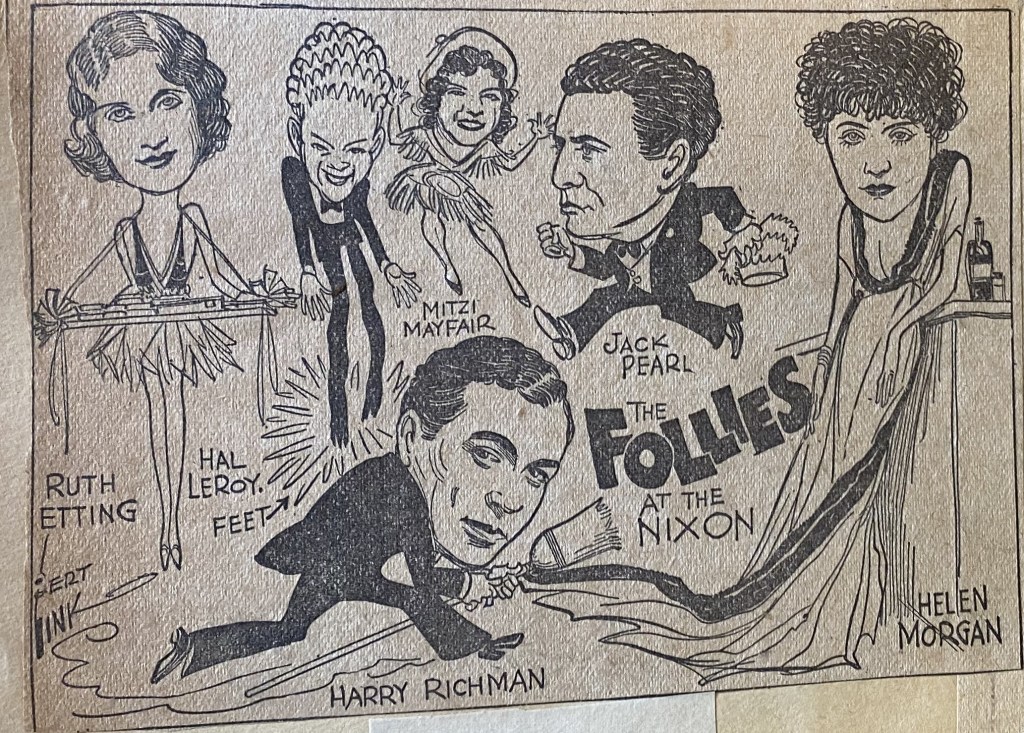

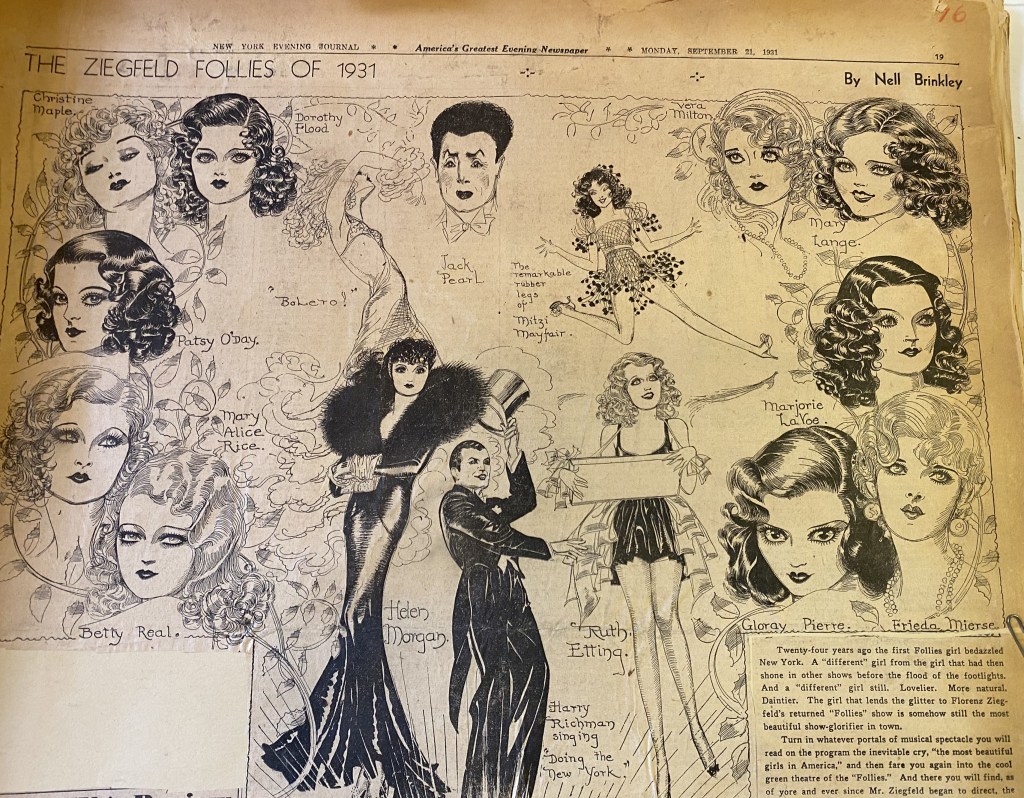

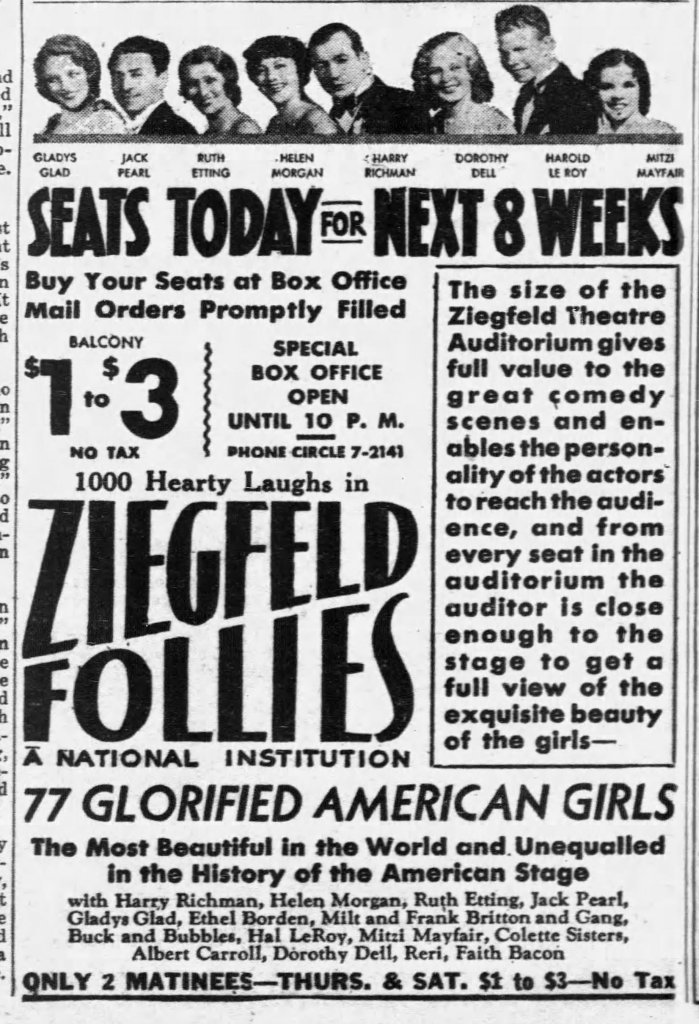

When the Follies chorus began rehearsals on May 7 and the principals some four days later, Ziegfeld still did not have a leading comedian. On the 20th, Variety announced that Jack Pearl had stepped into the troubled show.[viii] Others in the cast included Harry Richman and Faith Bacon, the latter recently arrested for overexposure in Earl Carroll’s Vanities. With a nod to changing tastes, Flo decided he wanted a Hollywood starlet to help boost box office. His initial choice was Jean Harlow, fresh from Public Enemy but not quite before the camera for her break-through role in Platinum Blonde.[ix] When Harlow failed to materialize, he went exotic, in the personage of the Polynesian dancer Reri (late of F. W. Murnau’s Tabu). Committed to making everything bigger, if not better, Ziegfeld upped the number of showgirls he employed from his customary sixty to eighty.[x] When asked why, he said he couldn’t say no to anyone in the depths of 1931 Depression America.[xi]

Ziegfeld originally chose Atlantic City as the premiere spot for his latest Follies.[xii] By the time the show went into rehearsals, it was clear the Apollo would not be able to handle the scenic demands of the show in its larval stage. The opening was moved to Boston, the site of many Follies premieres. On June 1, with the opening only two weeks away, Ziegfeld balked. The Boston controversy centered on the city’s Musicians’ Protective Association. Years before, the Association had passed a 60-40 rule that, in essence, required half again as many musicians be hired for any show as the score required. The rule, presumably, was used to provide the musician-equivalent of understudies. This edition of the Follies called for twenty musicians in the pit, and Ziegfeld was willing to hire thirty men at $72 a week. However, he refused to be responsible for their traveling expenses. Thomas B. Lothian and George Munroe, who represented the Erlanger and Shubert organizations, attempted to arbitrate between the two opposing sides, but when the Association refused to back down, Ziegfeld pulled the show from Boston.[xiii]

Cynical wags suspected Ziegfeld’s change in venue was more basic than that: he was broke and needed a theatre-crazy town close to New York where Ziegfeld was virtually guaranteed a sell-out in Depression-weary 1931.[xiv] Boston no longer fit the bill. Several eastern cities were considered, including Baltimore, Stanford, and Pittsburgh. Ziegfeld chose Pittsburgh, swayed by the Nixon’s healthy box-office returns on his previous productions there.[xv] The Nixon was also the birthplace of Whoopee, his last hit. Although the residents of Beantown were disappointed, the Three River City was delighted. Originally set to open on Thursday, June 11, for a nine-day run, the show was just not ready in time and was forced to postpone until the following Monday.[xvi]

While the $8,800 task of organizing a twelve railroad car caravan carrying sets, costumes and 202 people from New York to Pittsburgh was daunting enough, the cast unknowingly arrived in Pittsburgh during a taxi strike.[xvii] Even Ziegfeld found his trip from the rail station to the William Penn Hotel a challenge.[xviii]

Changes came fast and furious for everyone in Pittsburgh. With Richman and Jack Pearl hardly a match for previous Follies luminaries like Eddie Cantor, Will Rogers, Fannie Brice or Bert Williams, it came as no surprise that this edition was found lacking in comedy. The shakedown on sketches began with “Sophistication,” by Hellinger and Gene Buck. Another quick casualty was a prohibition screed called “Hic Hic Hooray.” Hellinger’s shockingly incorrect “The Africans Had a Word for It” was cut early on in Pittsburgh, only to be reinstated in time for the Broadway opening to have something bordering on the comic in the show. Dance, the show’s strongest suit, was beefed up when the Albertina Rasch Dancers received the second act ballet “Illusion in White” and Mitzi Mayfair was given another dance solo in the first act.

Quickly cut were Pearl Osgood’s two numbers, “Rhumba Baby” and her duet with Hal LeRoy, “Knock Knees.” With the cuts went Miss Osgood, who did not join the company in New York. A similar fate awaited Viola Tree. When the sequences “The French Dressmaker” and “At the Grand Guignol” were axed, so was Viola. Even her Dowager bit in the modern section of the “Broadway Reverie” playlet went away, with no one back-filling the role.[xix] Other musical changes included Earl Oxford’s trading in his “Waitin’ By the River” for “Sunny Southern Smile.” Harry Richman lost “Mailu,” which he sang with a group of sailors in the South Seas sequence which began the second act. He also lost “From Cradle to the Grave” and “Here We Are In Love,” his duet with Ruth Etting. Hal LeRoy and Mitzi Mayfair lost their young love duet, “Let’s Put Our Laundry in One Bag.”

For Helen, her two skits, “Victim of the Talkies” and the Grand Hotel parody were among the biggest hits in this Follies. Musically, the situation was far direr. Throughout the Pittsburgh and subsequent Broadway run, Helen and Flo shuffled in a dozen or more songs in search a hit number that forever proved elusive. One Morgan song, a duet with Harry Richman called “I’m With You” stayed in the production for the entire Broadway engagement. It was even recorded – but not by Helen Morgan.

(For more information of Helen’s work in the Follies, see https://www.kentuckypress.com/9781985900592/helen-morgan/).

Among the other songs to last through the Broadway run were Harry Richman’s opening number, “Help Yourself to Happiness” …

… and Dorothy Dell’s delightful celebration of a maid’s loss of virginity, “Was I?”

The only original cast member to preserve a vocal from this edition of the Follies was Ruth Etting. In the two-scene “Broadway Reverie” playlet, she appeared first, as Nora Bayes, circa 1915, singing “Shine on Harvest Moon.” This revival was the sole hit song from the 1931 Follies.

In the second scene, set in 1931, Etting followed “Was I?” with “Cigarettes, Cigars,” a retread of her previous hit, Rodgers and Hart’s “Ten Cents a Dance.”

Frustrated, Helen left the Follies on November 7, 1931, two weeks before it closed in New York. Ruth Etting did as well. Wini Shaw handled their material for the subsequent tour.

Ziegfeld entered talks to bring the 1931 Follies out west and film it. Nothing came of the idea. After the Follies tour ended in March 1932, he hired Bobby Connolly to reduce it to a tab unit: Ziegfeld’s Vaudeville Revue. Newly hired by RKO to shore up the dying Orpheum vaudeville circuit, Connolly prepped a company in the (currently dark) Broadway Theatre in New York, with the goal of slicing the production into three or four touring units. B.S. Moss expressed interest, as did Arthur Klein and Martin Beck, who wanted their own tab unit for their New York Palace stage. It is unclear whether Connolly, RKO, Moss, Klein, Beck, and Ziegfeld failed to come to terms, or if Flo himself pulled the plug on Ziegfeld’s Vaudeville Revue after the success of his 1932 radio program. In any event, he announced two live one-night stands of his own Follies of Long Ago, one on May 23 in Providence and the other on the following evening at the Boston Garden. No such events ever took place, let alone a tour.[xx]

Ziegfeld would never again work on a Follies.

This site serves as a companion to Helen Morgan: The Original Torch Singer and Ziegfeld’s Last Star, which was published on September 3, 2024.

[i] Variety, December 10, 1930 and January 14, 1931.

[ii] Variety, February 11, 1931.

[iii] Variety, January 14, 1931, 53 and February 4, 1931, 71.

[iv] Variety, April 15, 1931, p. 66

[v] New York Times, April 20, 1931, p. 16.

[vi] Los Angeles Times, February 10, 1931, p. A9.

[vii] “Broadway Banter,” The Atlanta Constitution, August 25, 1929, p. 20.

[viii] Variety, May 20, 1931, p. 132.

[ix] Variety, April 29, 1931, p. 2.

[x] Leiter, Samuel L. The Encyclopedia of the New York Stage, Greenwood Press, Westpoint, CT, 1989. p. 937.

[xi] Krug, Karl, The Pittsburgh Press , June 14, 1931

[xii] New York Times, April 25, 1931, p. 25.

[xiii] Variety, June 2, 1931, p. 52.

[xiv] Krug, Karl. “The Show Shops”, The Pittsburgh Press, June 7, 1931

[xv] Krug, Karl. “The Show Shops”, The Pittsburgh Press, May 31, 1931.

[xvi] Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 3, 1931.

[xvii] Krug, Karl, “The Show Shops”. Pittsburgh Press, June 15, 1931, p. 20.

[xviii] The Pittsburgh Press, June 13, 1931.

[xix] The Hartford Courant, July 5, 1931, p. D3.

[xx] Los Angeles Times, October 4, 1931 and Variety, April 12 and May 17, 1932

I knew there had to be a Connelly/Connolly connection!

By: Kevin on July 1, 2024

at 8:45 am