… 1939, Helen Morgan opened, out of town in A Night At the Moulin Rouge.

Helen began the 1939-40 season with high hopes as she seized an opportunity to bypass the clubs in order to make her living.

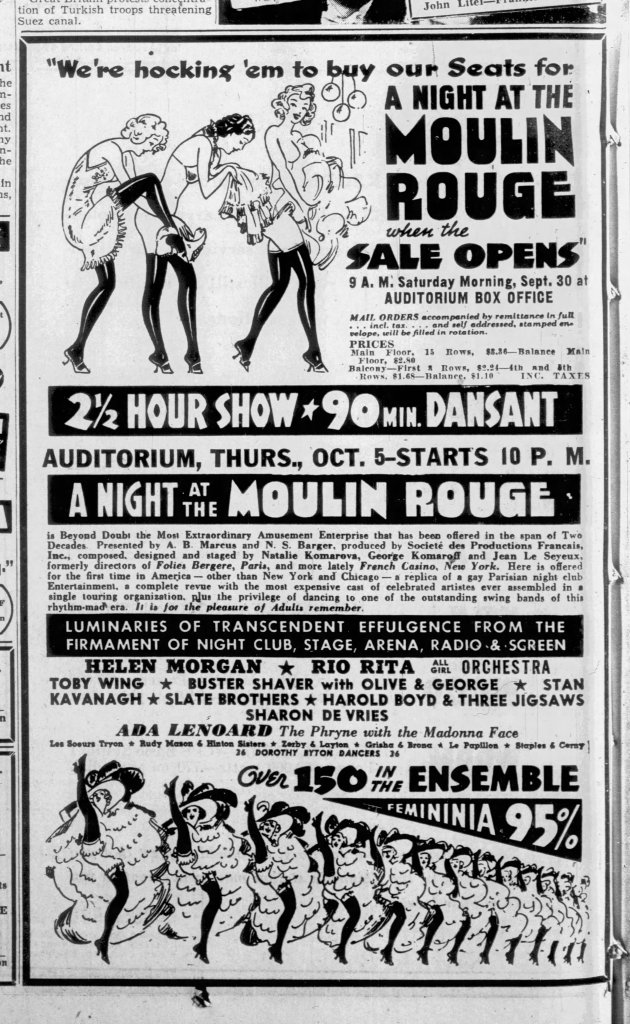

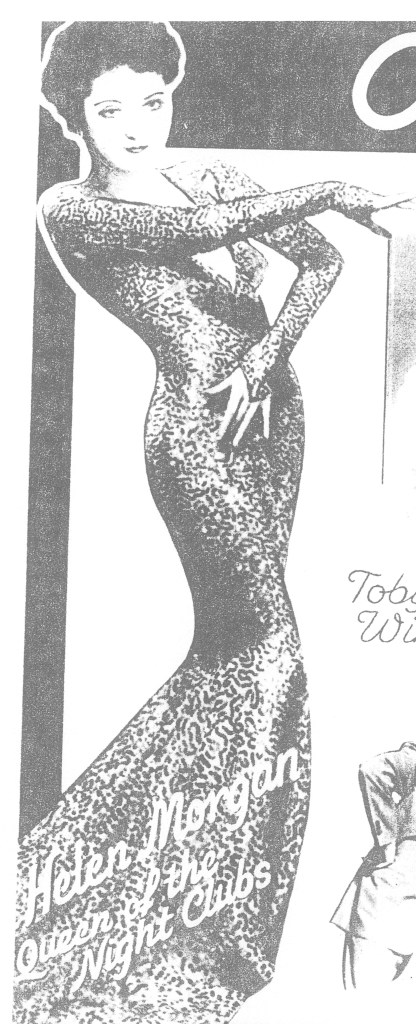

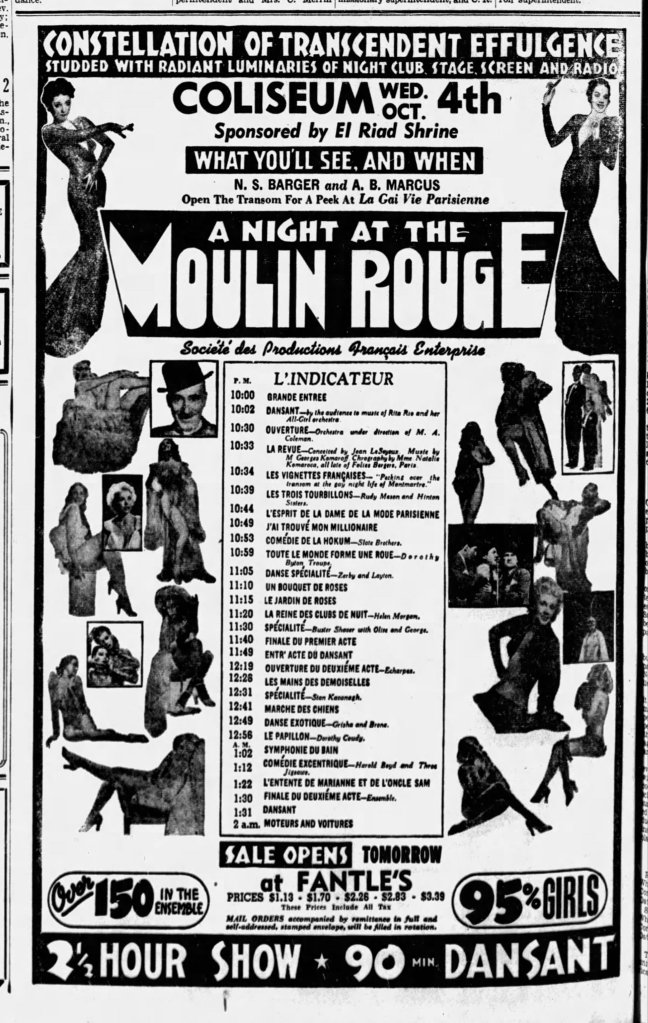

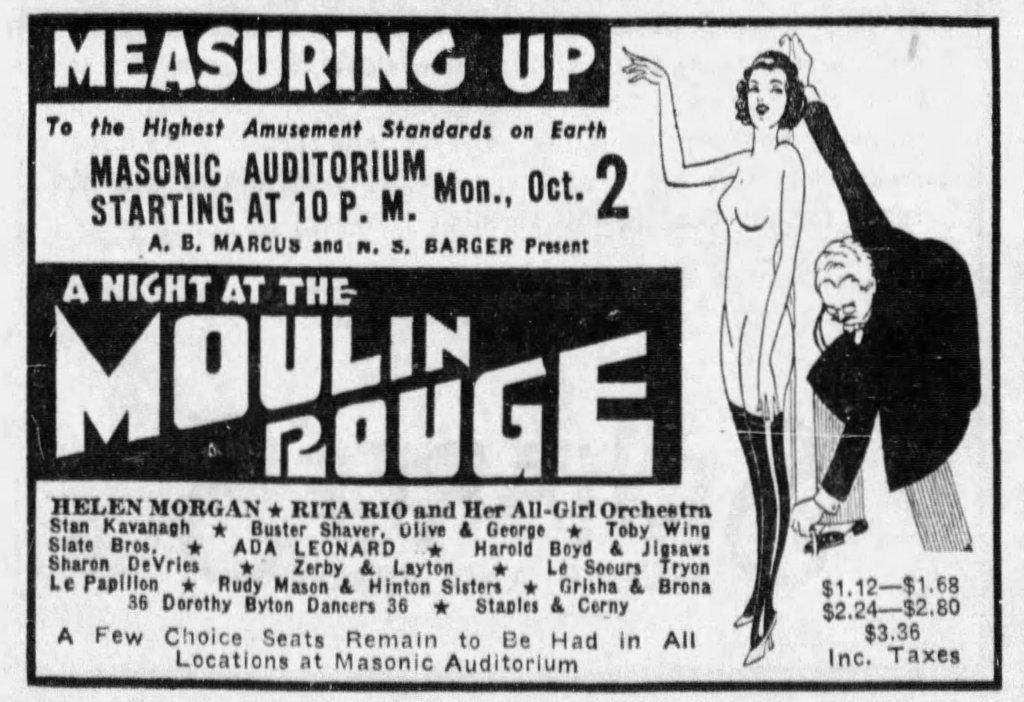

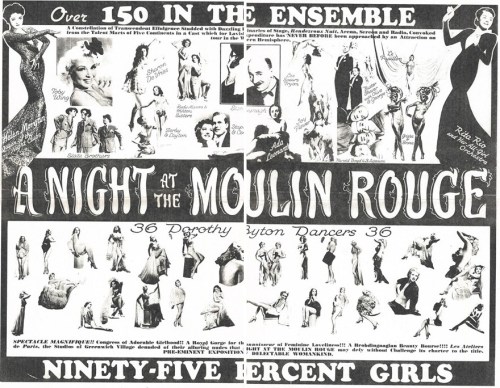

N. S. (Jack) Barger and A. B. Marcus’ A Night in the Moulin Rouge was a revue of elephantine proportions. With a cast of 150[i], even Helen, with the star billing as “Queen of the Nightclubs,” only received about eight minutes of stage time in a single appearance just before the first act finale (later moved to the second act). Singing four Show Boat numbers, Helen was on board solely for marquee value, but she did get the glamorous Spider Woman treatment in the show’s advertising.

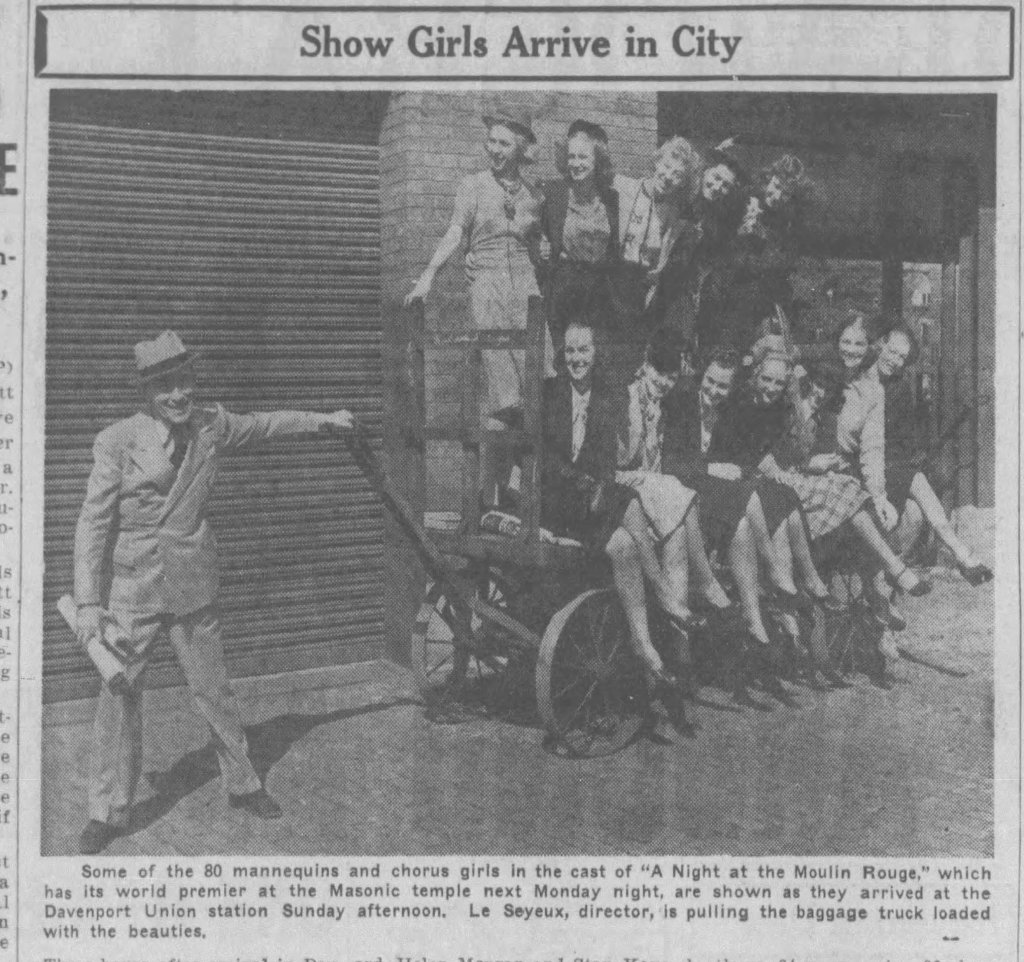

While she added nothing to the shape of the show,[ii] this was no cheaply assembled tab revue. Bankrolled at a reported $150,000, with over half of that allotted to 730 costumes that ran the gamut of stunning to camp, this was a big production. Originally in two acts and 23 scenes (later reduced to 18), Jean Le Seyeux, the composer of many of Maurice Chevalier’s French numbers and graduate of the Folies Begeres, conceived, designed, staged the production and supplied the Parisian pedigree. Natalie Komarova staged the dances, and George Komaroff conducted and supplied the nominal score. No one took credit for the book.

Early press releases hinted at a Broadway run, but luckily, the producers decided to wait. As it turned out, the New York’s World’s Fair overshadowed, instead of helped, and sent many quality productions from the 1939-40 Broadway season, including Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson in The Hot Mikado[iii] and George White’s final Broadway edition of his Scandals[iv] to early graves. Moulin Rouge opted for an extensive tour from stand to stand throughout the show-hungry mid-west, northwest and southwest.[v] Self-described as the largest touring production in years, the production would only rest for one two-week stand, in San Francisco during its Fair,[vi] to help iron out any kinks in the production prior to a New York bow, whenever that might be.

The hope of an eventual Broadway run induced the likes of Helen, Fifi D’Orsay, Toby Wing and juggler Stan Kavanaugh to sign.

Sweetening the deal was the fact that D’Orsay and Helen were old friends. Contrary to her stage persona, D’Orsay was not Parisian but was born and raised in Montreal. Helen befriended Fifi while the two began their careers in Quebec. A few years later when Helen was established in the nightclubs, Fifi moved to New York where she leaned on Helen for emotional and, one assumes, financial support. The opportunity to troupe together must have pleased Helen, but this was not to be. By the time the show finally went up, Fifi D’Orsay was not in the company.

With no more than a week of rehearsal, the production got off to a shaky start and never righted itself. With a complete lack of comprehension of life in the American Plains, the original plan was to adhere to a Parisienne schedule and open the doors at ten in the evening, start at 10:30, and continue the show until 1:30 before ending with a half hour of social dancing. In Iowa. On a Thursday night.[vii]

After a deluge of complaints at the box office, management announced the show would start a half-hour earlier. Instead, on the evening of October 2nd, the revue premiered in Davenport – a full hour late. It almost never opened. A month after Germany’s invasion of Poland, the cast rebelled at the notion of reviving George M. Cohan’s “Over There” for the flag-waving finale. Led by Buster Shaver and seconded by Toby Wing, the cast objected to the inference that it was only a matter of time before America was once again embroiled in Europe’s military actions. To end the standoff, Le Seyeaux agreed to let the cast sing Cohan’s final line as “We’ll stay right here ‘till it’s over, over there.”[viii]

Once the show started, rough spots were everywhere. Poor lighting undermined Helen’s single star turn. There was no sense of continuity, pacing or even structuring. Most of the acts, including Helen’s, seemed out of place or at least ill-fitted into the proceedings.

The following evening, the show bowed in Des Moines. Once again starting an hour late, the curtain did not come down until after midnight. The exhausted cast chose not to take a curtain call.[x] Although in trouble, the show was not hopeless. The costuming, particularly in the rose garden scene, was particularly effective. It needed focus and tightening.

First to go was the continental schedule. Curtain time was changed first to 9, then to the more American-friendly 8pm.

Rita Rio[xi] and her All-Girl Orchestra also failed to entice the audience up to dance. As originally planned, the Orchestra supplied dance music before and after the show and during intermission, in the manner of the old-time Montmartre nightclubs. In effect, Marcus and Barger attempted to provide two shows and four hours of entertainment for a single admission price. This might have worked in a large hall had the show resembled a huge floorshow, but in a legitimate theater setting, even in the barn-like civic auditoriums of the mid-west, coercing paying customers to break through the fourth wall and dance up on the stage proved too much to ask in Davenport or Des Moines. Within ten days, the dance section was dropped from the program, as was its top price of $3.30. With an additional trim of thirty minutes from the show itself, the evening’s running time was halved from four hours to two.[xii] By the end of October, tickets were scaled to a $2.75[xiii] high and Toby Wing and Rita Rio were gone. Wing, who had worked in film previously, retired. Rita Rio, a real life Julie LaVerne, went to Hollywood and, as Dona Drake, worked on film.

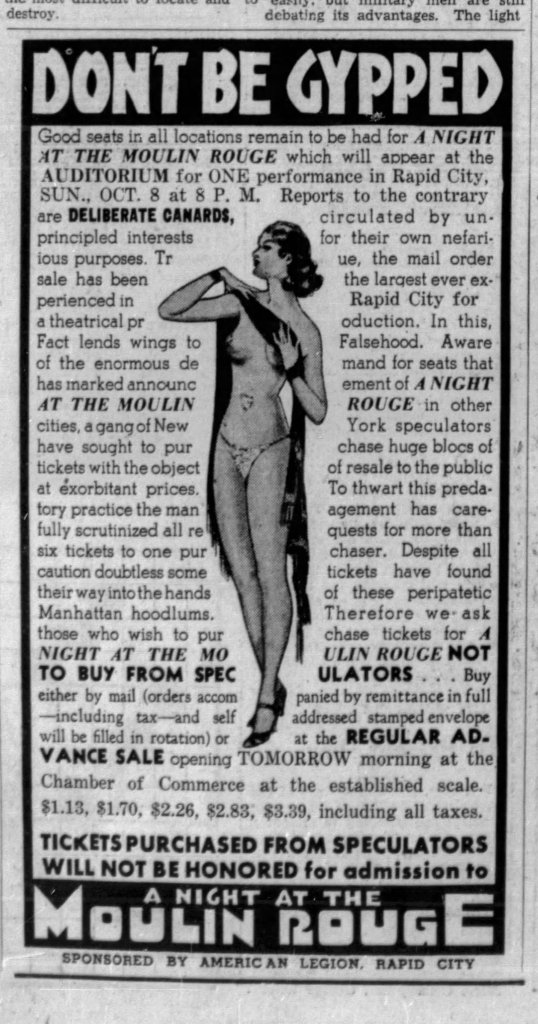

As it toured the mid-west, then the northwest, the production’s luck proved to be as spotty as the show. The special seven car train (three baggage cars, four Pullmans and a dining car) used to transport the show from town to town had difficulty keeping to its daunting schedule. It arrived in Denver two hours late, placing the Friday night premiere there in peril. Stagehands were still loading in at curtain time, but the show went on.[xiv] In an attempt to titillate the tired businessmen in cities like Portland, Oregon and Seattle, the show often found itself on the outs with church groups who, sight unseen, found the show’s merits to be dubious.

In Seattle, religious groups pressured the mayor to ban the show from the city’s Civic Auditorium. It played instead in the privately owned Music Hall Theatre.[xv] All in all, the alleged impropriety of the show usually worked against it at the box office.

A Night in the Moulin Rouge even ran into trouble in San Francisco where, due to a serious booking error, it played opposite the Folies Bergeres which was concluding its very successful six-week run at the California Auditorium. Originally scheduled to play two full weeks, Marcus and Barger instead attempted to minimize the damage by coming in on Friday of the first week and playing for only ten days. A midnight show on the 28th for the USC and UC Football teams[xvi] may have helped, but the grosses for both shows during their competition told the story: Folies Bergeres: $34,200, A Night in the Moulin Rouge: $13,000.[xvii] When the biggest notice in a review concerns a Great Dane mistaking the painted fire hydrant on a drop for the real thing, something is wrong.[xviii]

The show endured a nine-day hiatus, during which Helen visited Los Angeles and partied at the It Café, and, presumably, with her current flame, Dr. Frank Nolan. When asked to honor the patrons with a song or two, she was happy to give the club a free concert.[xix] Helen’s public was less pleased earlier in the tour. One night, as she was in Sioux City, Morgan entered her hotel’s dining room. She was asked to honor the crowd with a song and she gamely approached the small combo and asked if they knew any of her numbers. They did, but when she asked them to play them in her keys the band announced they could not transpose on the fly. Unwilling to risk it, Helen regretfully reclined and returned to her seat.

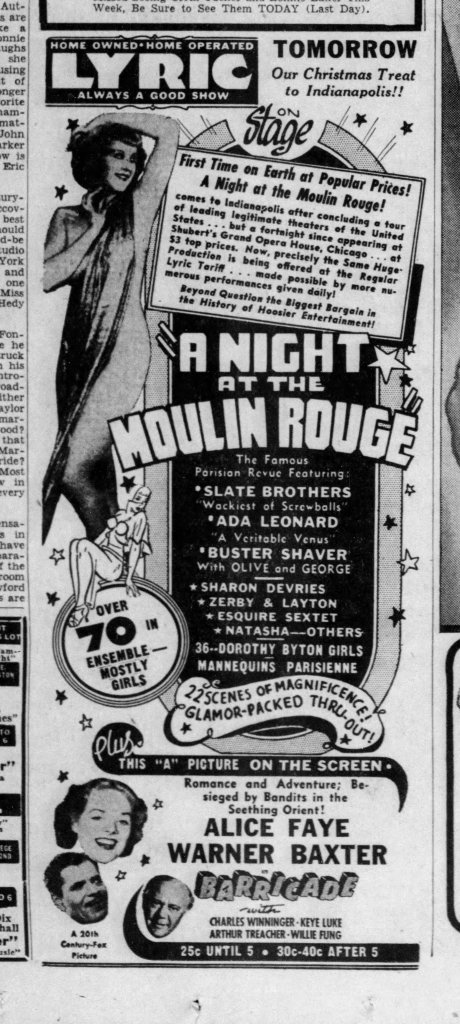

Licking its wounds, the show limped through Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas and Missouri before enduring a disastrous Thanksgiving week at Chicago’s Grand Opera House. The paltry gross was only $8,000. Making matters worse, Helen, along with fellow cast members Ada Leonard, Stan Kavanaugh and the Slate Brothers were brought up in front of the Theater Authority for playing an unauthorized benefit while in the Windy City.[xxiii]

Management converted the production and toured as a tabloid revue.[xxiv]

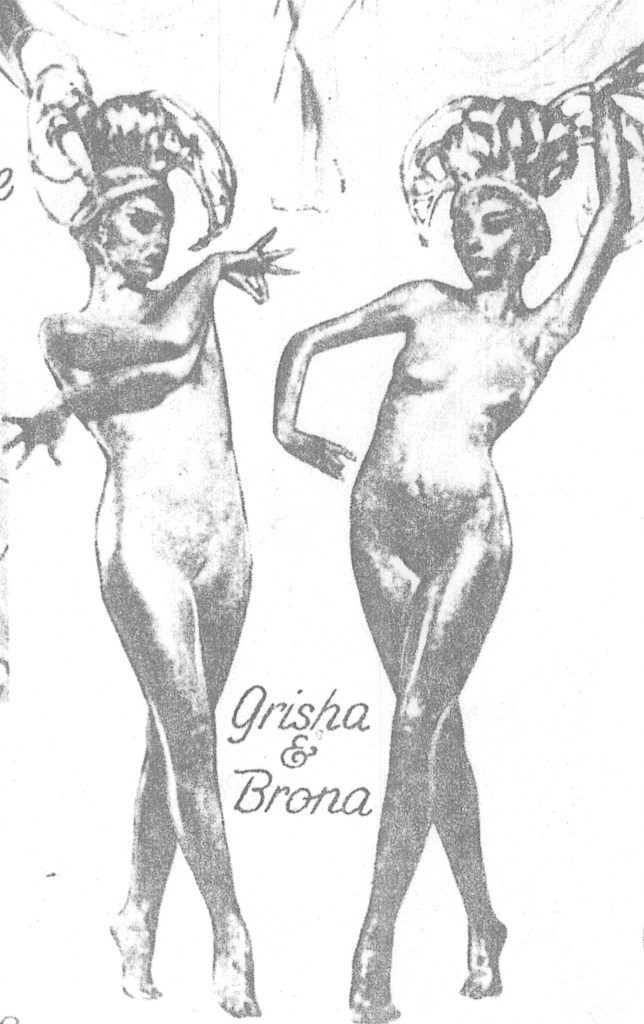

Helen was thankfully trimmed. Even scaled down, the show only limped along until the middle of March, where it went belly-up in Atlanta.[xxv] With never an unkind word to say about anyone, Helen tried to be philosophical about Moulin Rouge. “It was a good show. It had a lot of good things in it. But it started off on the wrong foot and just kept bumbling along. I just did my own stuff, sang a couple of numbers. I might have been in vaudeville as far as I was concerned.”[xxvi] Straight vaudeville, even in 1939, would have been preferable to, as Helen later described it, a “French-type concoction that didn’t jell.” That was a nice way of describing an entertainment, complete with strip numbers, that bore more resemblance to burlesque than a 30s revue (the team of Grisha and Brons danced once in cellophane and, later, as the “golden Buddahs,” in gild.)[xxvii]

Not everything in the show was hopeless. Grisha and Brons received good notices, as did Natacha in a slave girl dance. The scenery for a Beach Symphony was well received, as was the windmill scene and the “Voices in the Dark” sequence.[xxviii] But the misses outweighed the hits in a production that relied on sex and spectacle without the class that Ziegfeld was able to bring to his Follies. In any event, the Follies had been hopelessly dated for the better part of a decade. Successful revues of the 30s were sophisticated and satirical. A Night in the Moulin Rouge was neither. But it did offer diverting advertisements.

This site serves as a companion to the book Helen Morgan: The Original Torch Singer and Ziegfeld’s Last Star.

[i] Variety, October 21, 1939

[ii] Tulsa Daily World, November 25, 1939, p. 5.

[iii] The Hot Mikado (3-23-1939, Broadhurst)

[iv] George White’s Scandals of 1939 (8-28-1939, Alvin)

[v] Unidentified flyer for A Night in the Moulin Rouge.

[vi] Variety, July 19, 1939, p. 41.

[vii] Daily Argus-Leader, Sioux Falls, SD, September 28, 1939, p. 18.

[viii] Des Moines Register, October 3, 1939, p. 15.

[ix] Weber, The Billboard, October 14, 1939, p. 5 & 60.

[x] Hoschar, Allen, “Ragged Night at Moulin Rouge,” Des Moines Register, October 4, 1939, p. 1-A.

[xi] Born Rita Novella, Rita moved into films following An Evening in the Moulin Rouge. As Dona Drake she appeared in The Road to Morocco, Louisiana Purchase, Let’s Face It and others.

[xii] Montana Standard, Butte Montana, October 11, 1939, p. 4.

[xiii] Variety, October 25, 1939, p. 49.

[xiv] Denver Post, October 7, 1939, p. 9.

[xv] The Spokesman-Review, Spokane Washington, October 10, 1039, p. 5.

[xvi] Oakland Tribune, October 20, 1939, p. 26.

[xvii] The Billboard, November 18, 1939, p. 20.

[xviii] Oakland Tribune, October 24, 1939, p. 13.

[xix] The Hayward Daily Review, November 1, 1939.

[xx] San Antonio Express, November 5, 1939.

[xxi] Variety, July 19(?) 1939.

[xxii] Variety, review by Andy, November 15(?) 1939.

[xxiii] Chicago Daily Tribune, December 14, 1939, p. 18.

[xxiv] Variety, December 2, 1939.

[xxv] The Billboard, March 2, 1940, p. 23 and March 23, 1940, p. 17.

[xxvi] Arnold, Elliott, New York Telegram, March 9, 1940.

[xxvii] Hoschar, Allen, “Ragged Night at Moulin Rouge,” Des Moines Register, October 4, 1939, p. 1-A.

[xxviii] Wichita Eagle, November 22, 1939, p. 6.

Leave a comment